Today I would like to share a very successful lesson I created for a B2 (upper-intermediate) group around the topic of climate change and this article by The Guardian. This is a very rough plan and needs fine-tuning, mainly to suit your learners needs and interests. I have used this lesson with both adults and teenagers, and it has worked well in both cases.

Aims: by the end of the lesson, students will have revised vocabulary linked to climate change and the environment, will have practised reading an authentic text and will have discussed actions to fight climate change.

Time: 60-80 minutes

Stage 1: lexis revision

Write on the board the words CLIMATE CHANGE. Ss in pairs brainstorm words related to the topic. During feedback, write words on the board for reference during the following stages and clarify meaning/pronunciation if necessary. You can add words such as blizzard, famine, endangered species, carbon footprint, global warming and any other lexis you anticipate they might need for the following stages.

Optional lexis work: ask Ss to write 5 sentences using some of the words on the board. They then read the sentences to each other and compare ideas.

Stage 2: small group discussion

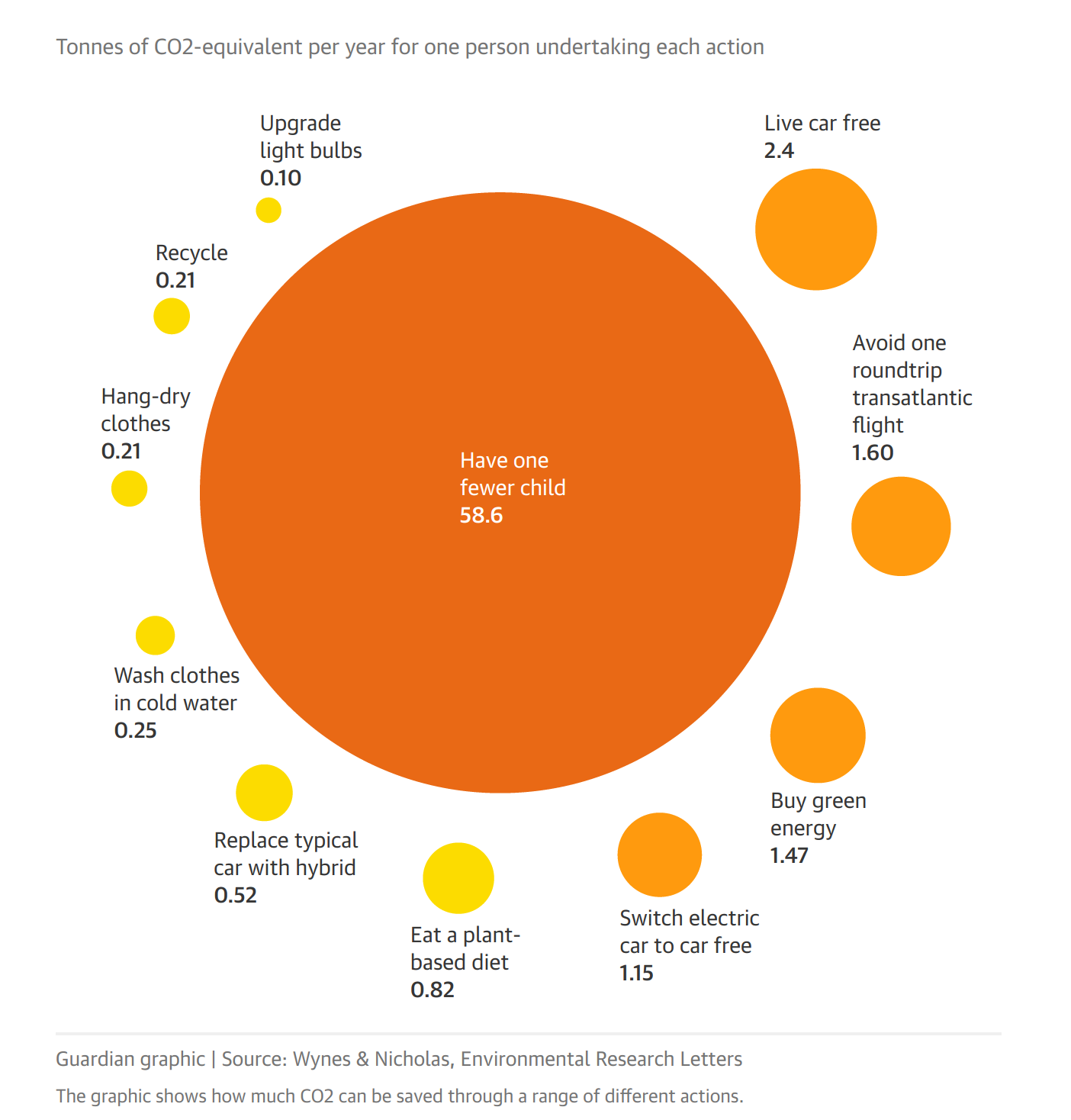

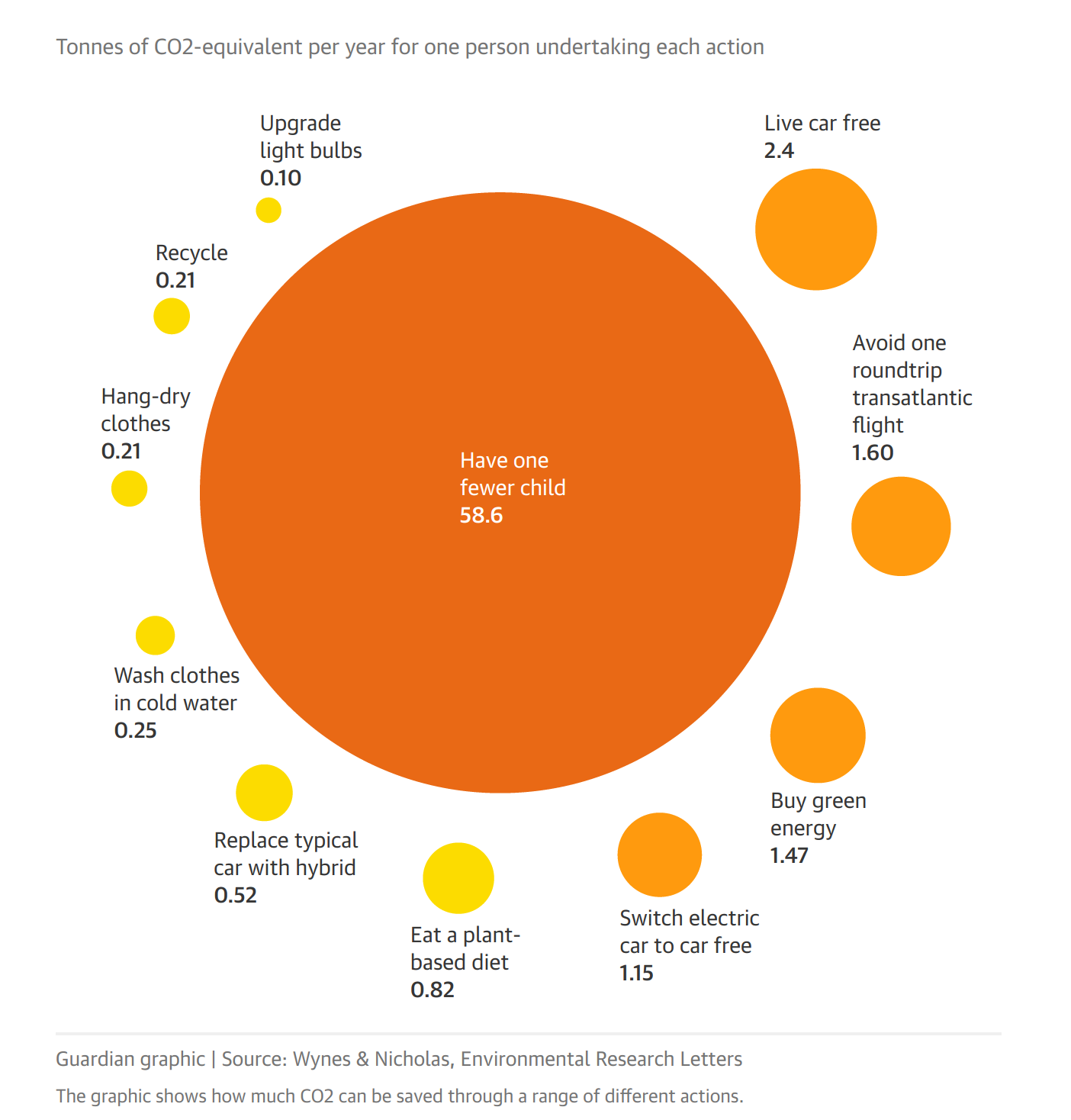

Divide your class into small groups. Explain that The Guardian has published an article detailing the most significant steps individuals can take to fight global warming. Tell Ss their job is to predict what steps might be in the article. I generally ask Ss to compile a list of the 5 actions they think are most effective in fighting global warming, as well as the reasons why they think these actions are so effective.

During this stage, you can monitor and help with language, as well as take notes on any gaps you will want to work on later on in the lesson or in the future.

Stage 3: whole class / bigger group discussion

Once all the groups have finished, depending on your class size, you can choose to pair up groups to create larger groups, or do this stage open class (in which case I make Ss sit in a circle, and I sit in a corner of the room as ‘audience’).

The groups compare their lists and have to negotiate a common 5-item list of effective actions to fight climate change. Monitor for use of specific lexis you revised in stage 1. If you find/know that some students tend to monopolise the conversation, you can set specific rules such as one person can not argue for or against more than one/two points in the list, or can not speak again until all other members of the group have expressed their opinion.

Stage 4: content feedback

When the discussion has come to an end, and the groups/class have decided on 5 actions they think are the most effective, give Ss this handout* (explaining it is the article you previously mentioned) and ask them to read it first to find out if any of the points in their lists are mentioned in the article. Have an open class discussion to see which group get most points similar to the article and/or if any of the points mentioned in the article surprised them.

Optionally, you can also ask Ss to read the article again, and now write a list of the 5 most effective actions according to the research reported in the article. They could do this individually or in pairs. During this stage I circulate and help with difficult language, trying to encourage Ss to understand from the context when possible.

When they all have finished, compare ideas open class. At this stage, I generally show the graphics from the article and collect Ss reaction to the article and to the graphics.

Stage 5: language feedback

At this point, you can put on the board any language that has come up during previous stages, such as correct or inappropriate use of the target lexis presented in stage 1, or any other language that has been focus of your previous lessons.

That’s all, I hope you find some useful ideas in this post, and if you try out the lesson please let me know how it goes and how you tweaked it.

*please note that in this handout I deleted some parts of the article to make it less intimidating for the students.